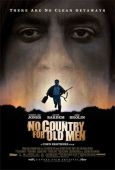

I almost missed my chance to see this movie in theatres, because life was so busy when the movie was released five weeks ago that it came and went before I had the chance. But since I first heard about it, No Country has been nominated for four Golden Globes and eighteen other awards, and has gone on to win another twenty-nine awards in the process. So, my local multiplex had good reason to bring it back over Christmas and, in a fit of excitement, I ran out to see it last night.

I almost missed my chance to see this movie in theatres, because life was so busy when the movie was released five weeks ago that it came and went before I had the chance. But since I first heard about it, No Country has been nominated for four Golden Globes and eighteen other awards, and has gone on to win another twenty-nine awards in the process. So, my local multiplex had good reason to bring it back over Christmas and, in a fit of excitement, I ran out to see it last night.

I always keep an eye on what the Coen brothers are working on. (Right now, for example, they’re post-producing Burn After Reading and pre-producing A Serious Man.) I’m a huge fan of their work: Raising Arizona, Fargo, O Brother, even Ladykillers, and No Country fits right into the Coen library. As Andrew Wright says, “Five minutes in, it already feels like a classic.”

Like many of the others, it both honours and satirises the region of the United States in which its story takes place, in this instance 1980 Texas near the border with Mexico, complete with exaggerated accents, landscape and dress codes. This gives it a certain ‘feel’. Like the others, it’s violent and contains darkly comic themes with a kind of mythology undergirding the story. Like the others it involves criminality, greed, misunderstanding, the downtrodden, the “unstoppable evil” and the depiction of a tragic American life. Like the others, it’s somewhat stylised and intentionally ‘brands the mind’ with a particular feature or idiosyncrasy: in this case what the woodchipper was to Fargo, so a ‘captive bolt pistol’ is to No Country.

I’d best explain this last point. Indeed it’s been amusing to see the critics try to do so. A ‘captive bolt pistol’ is a device used in the slaughter of cattle and other livestock. In the film, it looks like an oxygen tank that someone may carry around to breathe from, but instead of a mask at the end of its hose, it has a metal valve on the end which contains a sharp, spring-loaded bolt at its tip. When the lever is pressed, the compressed air rushes from the tank through the hose and jolts the bolt forward into the brain of whichever animal is being slaughtered. The villain in No Country doesn’t use it for livestock, of course. He uses it in conjunction with a sawn-off shotgun with a shiny steel silencer on the end, making both his weapons items which most filmgoers won’t have seen before. These weapons will be icons of cinema in coming years if this movie becomes a classic; whenever anybody mentions No Country For Old Men people will say, ‘Oh, the movie with the air weapon and the silencer shotgun.’ (Perhaps by that stage the Brady Campaign will have tried to ban captive bolt pistols on the basis that people may use them to commit crimes? Or if they haven’t, PETA may have done it for them.)

I’d best explain this last point. Indeed it’s been amusing to see the critics try to do so. A ‘captive bolt pistol’ is a device used in the slaughter of cattle and other livestock. In the film, it looks like an oxygen tank that someone may carry around to breathe from, but instead of a mask at the end of its hose, it has a metal valve on the end which contains a sharp, spring-loaded bolt at its tip. When the lever is pressed, the compressed air rushes from the tank through the hose and jolts the bolt forward into the brain of whichever animal is being slaughtered. The villain in No Country doesn’t use it for livestock, of course. He uses it in conjunction with a sawn-off shotgun with a shiny steel silencer on the end, making both his weapons items which most filmgoers won’t have seen before. These weapons will be icons of cinema in coming years if this movie becomes a classic; whenever anybody mentions No Country For Old Men people will say, ‘Oh, the movie with the air weapon and the silencer shotgun.’ (Perhaps by that stage the Brady Campaign will have tried to ban captive bolt pistols on the basis that people may use them to commit crimes? Or if they haven’t, PETA may have done it for them.)

But it is the guy who wields those weapons that you’ll remember most. He has already been described as “one of the most inexplicably frightening figures in cinematic history”. I can’t disagree. He’s quietly ominous, and the star of the show. And the show is great. The Coens are on form, the story compelling, the landscape bleak, the psycho with the cattle killer menacing and insanely threatening, and Tommy Lee Jones wonderful as the county sheriff. It’s a strange world that these characters occupy, and I’m sure it bears some resemblance to how a group of strange, unsavoury Texans may have lived in 1980.

One other thing: there’s very little music, which makes the film all the more unsettling and surreal. You might be forgiven for thinking that the score would be important in this movie. After all, O Brother Where Art Thou? was one of the only films whose soundtrack made more money than the movie did. But it just isn’t Coen-like to let the details of such prior success interfere in their current artistic endeavours. Subtlety rules the soundtrack: atmosphere, white noise and effects, rather than music. This adds to the realism, enhances the ominousness, punctuates the story, intensifies the general unease with which the plot is presented. And the ‘captive bolt pistol’ sounds fantastic.

Finally, let me share with you the scene that made the most marked impression on me. It’s when the psycho bad guy walks into a small, old-fashioned gas station convenience store in the middle of nowhere, to the instant discomfort of the gentleman behind the counter. The dialogue is riveting, and the ambience electric. When our villain tosses a coin and asks the owner to ‘call’, the entire audience knows without a shadow of a doubt that he’s a nuclear bomb that can be triggered inadvertently at any moment by the slightest chemical change within his brain, and that the answer the gentleman gives – ‘heads’ or ‘tails’ – will either save his life or kill him instantly in a radioactive wrath of rationalised principle (perhaps by cow gun). Yet the conversation is civil, and consistent, and almost completely incomprehensible. It’s brilliant.

There are a lot of reviews of this film. One of the best amateur discussions of No Country is by Pete-230 on IMDB: “Strongest examination of evil since Silence of the Lambs.” And that’s what it is: an examination of evil, with strong symbolic and mythological undertones. Recommended.