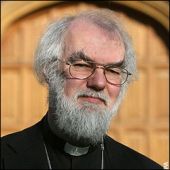

As Crawley reports this morning, it appears Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams has trodden on a landmine of British legality with some comments made as part of his foundation lecture at the Royal Courts of Justice.

As Crawley reports this morning, it appears Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams has trodden on a landmine of British legality with some comments made as part of his foundation lecture at the Royal Courts of Justice.

In short, Williams’ comments are a thoughtful discussion-opener on the question of whether the United Kingdom should allow Muslim communities to be governed under sharia law. His general apparent openness to the idea has irked some. As Crawley reports:

“Some commentators say this breaks apart a fundamental legal principle, namely, that all UK citizens should be governed by the same laws. Since the UK includes more than one legal system, with sometimes significant variations in both criminal and civil law, this principle would not appear to be threatened (or any more threatened than at present). In the US, opt-outs already exist in some states for those native Americans who wish to have a particular case processed in a native American court, with the courts ruling recognised as a binding judgment in law. Why couldn’t such a provision be granted within the UK?”

Well, I think the very idea is imprudent. I’ll attempt to offer the summary of a libertarian response in a moment, but at first glance it appears to furnish yet further proof of what Stephen Graham has argued often: that what some minorities appear to demand isn’t “equal rights” at all, but rather “special rights.” Of course sharia law may not be an enviable law to live under from a western standpoint, but it nevertheless creates two standards of justice, and I think that’s the problem. It begs the question of what ethos exactly law is based upon, and whether that ethos is universally applicable, perhaps from appeal to human rights, or not.

Let me part with the main discussion for a second to say that the comparison with native Americans doesn’t work for me either. I live beside an American Indian reservation and am very familiar with the jurisdictional issues; they only make sense within the context of American history (native Americans were ‘native’!) and the already diverse, tiered American justice system which involves courts at many different levels from local to federal — even then, it’s reaching.

But this seems to breach another debate about the nature of the immigration currently occurring in the UK. It seems to me that there are sections of UK society that don’t know whether it’s right to expect immigrants to adapt to their new country and do things differently, as British people would if they were moving in the other direction. Why is there this double standard? And if Muslims want sharia law, can’t they vote for their candidates like everyone else in an attempt to change things democratically? Or is that expecting unfairly of people who do not necessarily share democratic values? Is democracy a value by which all UK citizens must live, or is it, too, something which Muslim communities may “opt-out” of, in favour of the kind of government imposed on the people of Islamic nations?

Isn’t the bottom line here that if a person immigrates from one country to another then they should expect to adopt the principles by which that country makes its laws? And if they don’t like those principles and decide to immigrate anyway, shouldn’t they make the changes they want through the representative process? One thing’s for sure: they wouldn’t even have a voice to say what they think if they lived in many of the nations that currently are governed by sharia law.

Again, I’m happy that libertarianism provides the best answer. A minimalist law, based upon rights alone, ensures the freedom of all citizens to act within whatever religious or ethical code they wish (so long as that does no infringe on the equal rights of other citizens). Libertarians would support Muslims the right to practice their religion and organise into groups and submit to each others’ laws, without affecting the role of the justice system in protecting those rights and ruling on infringements thereof. If rights are incontrovertible – and they are – then no variations of law can justifiably infringe on them, and that’s what Rowan Williams patently doesn’t acknowledge.

If Muslims want a system of government based upon sharia law, there are Islamic countries which embody those very values. But the United Kingdom, if it wishes to be a free nation, should instead embody the values of freedom and human rights, which guarantee every religious group the liberty to practice their religion without need of compromise or jurisdictional segregation.

I should finish by saying that Williams’ comments are not deserving of this backlash; his lecture was a sensible, reasonable and thoughtful discourse on the issue. He is wrong, in my opinion, but his speech was a useful introduction to the debate and is well worth reading.

———————

Added 4:46pm: Matthew Parris has an excellent piece in today’s Times newspaper here in which he teases out this response some more. I love the opening paragraphs:

You say,†said Lord Napier (confronted as Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in India by locals protesting against the suppression of suttee) “that it is your custom to burn widows. Very well. We also have a custom: when men burn a woman alive, we tie a rope around their necks and we hang them. Build your funeral pyre; beside it, my carpenters will build a gallows. You may follow your custom. And then we will follow ours.â€

The present Archbishop of Canterbury is no Napier. He was not, however, proposing tolerance for the wilder excesses of Sharia, let alone suttee, in his speech on Thursday. Rowan Williams is not in favour of letting people stone adultresses, or chop off thieves’ hands, or force the marriages of daughters. He made it clear that a line must be drawn. But he failed to say why or how. And it is that failure that marks what I hope is just the incoherence – but fear may be the disingenuousness – of the Archbishop’s argument.